GOSPEL

I attended Sunday school across the street from our house in Chicago. This was a Lutheran congregation influenced by the Nineteenth Century evangelist Dwight Moody, who emphasized Christian teachings of peace, love, and easy redemption through personal prayer.

Good Gospel News! But my religious life seemed to involve a lot of guilt. Our home that was wracked by parental arguments. My prayer for a world then at war in Korea was, “Why can’t everyone get along and just be nice to each other?” The role model of Christ as a martyr, peacemaker and healer was a challenging one. I remember the Bible quotes repeated by my mother.

- The Golden Rule: Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

- Love thy neighbor as thyself.

- Love your enemy and turn the other cheek.

- Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors.

- Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the Earth.

- It’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter Heaven.

These proverbs seemed to be the formulas for a harmonious life. Wouldn’t everyone want to embrace them? Other sayings were more problematic.

- “Now I lay me down to sleep; I pray the Lord my soul to keep. If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take.” Morbid if you think too much about it.

- “It’s the thought that counts.” But on the other hand, “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions.”

“And God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life.” We memorized John 3:16 from the New Testament, because it forms the basis of the eternal reward and punishment system that has powered Christ’s church and the evangelistic rebirth movement. Other glimpses of afterlife are rare in the Bible, though they’re vivid in ecclesiastic art and preaching.

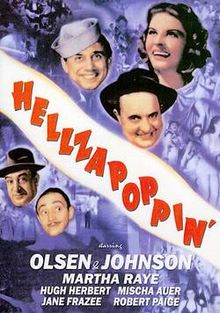

To me, just dying was scary enough. But along with the comforting promise of eternal life, I was warned of an underworld of permanent suffering and torture for sinners, or at least the unrepentant. I don’t recall whether I learned this in church or from pop culture. There was this ad for a musical called Hellzapoppin’. I found myself morbidly fascinated with the idea of Hell. Through its association with adult things such as drink, gambling, profanity and unguessed forbidden pleasures, it had a weird attraction for me. Sort of a sado-masochistic preview of Gitmo or Abu Grahib.

The only physical suffering I experienced, aside from the Chicago heat or bumping my head, was tickle-torture. I also felt guilt over hurtful things I said, petty thefts or disobedience, and wicked thoughts. One time I took the dollar I’d forgotten to give for a church offering and spent it on a 10-cent cap pistol and 90 rolls of caps. A major guilt, especially after the store lady got on the phone to my mother. Fortunately, both of my parents urged me not to blame myself over the adult problems that led to their separation and divorce.

Later in childhood, my musing about order and purpose in the universe focused on astronomical questions and my newfound love of science fiction: Was there really life on other planets? As a little kid, I swore breathlessly to my parents that I’d seen a flying saucer winking colored lights over Chicago, and then had nightmares about green cavemen scaling the walls of our 3-story walkup. But now I feared we might be alone in the universe, with no interesting aliens and no hospitable places to land our spaceships. Then I had an epiphany. I told my father, yes, I believed there was alien life. Otherwise, what did all those other stars and planets exist for?

This, of course, supposed that the universe had been created for a purpose. It’s called teleological reasoning, creation for use rather than by cause, and in science it’s regarded as a fallacy. Still it eased my fears about a barren cosmos. My concern for alien beings was based on the notion that, if they traveled in outer space and contacted us, they must have achieved a stable home world and a peaceful, enlightened society. This would make them helpful teachers and exemplars for our war-torn planet – something like the human Star Trekkers later portrayed on TV as dealing with alien races under a benevolent Prime Directive.

Yet I’d also seen a sci fi novel titled Invaders from Earth, where primitive Martian innocents were vilified and attacked by Earth colonists…a shame, but not such a scary threat, so long as we were the oppressors.

These cosmological ideas remained vague until my senior year in high school. Meanwhile my church attendance ceased. Never did it occur to me that aliens would come to Earth heralding Christian belief, like the Three Kings. I still retained a strong, tormenting guilt over my sexual yearnings and solitary practices, but this sense of shame and unworthiness came more from the Boy Scout Handbook than from any church or fear of damnation. How could God fairly punish me for my weakness if he made me this way? I never felt that I’d been personally tempted by the Devil.

My father’s views on spirituality were similarly obscure. He had briefly searched for Ancient Wisdom as a Rosicrucian, taking me to their Egyptian Museum in San Jose, and wangling a bargain price on the books (which weren’t adventurous enough for me to read.) As a typesetter educated mainly by newspapers, Dad once held up his hand and said, “Son, look at this, how it can move and grip, play music and do surgery. To me, the human hand is all the proof we need that there is a great designer out there who made this marvelous tool for us.” Fortunately, I didn’t have the resources to bring him a picture of an ape’s hand, and before that a rat’s paw and fish fin, to show how it had evolved down the ages. Would that have destroyed his faith, or kindled a new one?

My dad’s views on family life, by contrast, were based partly on ape’s habits, how the young gorilla always wanted to kill off the old silverback, to take his place as master of the harem. So evidently he was an evolutionist, more than me. We may have had a primal Oedipus thing going, but if so it was his complex, not mine.

After all this religious tutelage, coming of age in High School at 17, I took Biology 2, a specially challenging college-level course. After paper chromatography we studied natural selection, not genetic but inter-species, short-term in a tiny ecosystem. We were sent forth in pairs to obtain a small vial of ditch water, which we then uncorked and studied over a period of weeks under a microscope. The wet slides that we made daily from a single droplet showed teeming, pulsating life, a mass of simple algae cruised by occasional unicellular animals.

As we sketched the different life forms and recorded sample counts, we discovered new protozoans that had been scarce in the original samples, slipper-shaped paramecia and hungry rotifers that scoured up the lesser animalcules like a Hoover vacuum cleaner. Our tiny microcosm of ecology changed over time, and presumably deteriorated. Life in the droplet samples became scarce except for the occasional large, scary predator darting through our microscope field.

My experience of this natural world was all the more vivid due to embarking on my own process of selection and reproduction with my lab partner, Cheryl, who became my wife and companion of 50 years, till death did us part.

After this very compelling glimpse of the life process, our class turned to the detailed study of genetics, for which Crick and Watson had won the Nobel Prize two years earlier in 1962. With our basic knowledge of chemistry aided by diagrams in the text and on the chalkboard, we were able to see how the interaction of RNA and DNA, ribonucleic acid and de-oxy ribonucleic acid, were able to replicate and separate the strands of organic chemicals to control growth of single-celled organisms, or of stem cells which later diversify into the specialized tissues of a multi-cellular being.

Seeing this, I could then understand how a random mutation to the chemical string, in the rare case where it did not damage or kill the organism, could provide a favorable mutation and promote survival and reproduction, to the exclusion of less viable gene expressions. It became clear that, in the absence of a guiding spirit or intellect, all that was needed, here in Earth’s hospitable seas and wetlands was time. A lot of it, almost unimaginable ages—the vast, echoing cathedral of our planet’s geological and biological eons. Here indeed is Ancient Wisdom, more miraculous than anything dreamt of by the Egyptians or Israelites.

The first effect of this revelation on my young mind was predictable. So, great! There’s no creator God or divine will in the world, so I can do whatever I want. I can be a savage barbarian, a swindler, or a tyrant if I’m clever enough to get away with it. Much like on Wall Street today—I expressed these views to my girlfriend and boy friends, even in earshot of our biology teacher on a bus trip. He must have been bemused, because he was a regular church-goer.

But whoa up there, Nelly! For one thing, I’d been raised with Christian ideals of peace and brotherhood, which I still revered. They fit into my world views of fair play, equal opportunity and meritocracy. The most important thing to me was the esteem of my friends and teachers, whom I didn’t think would honor a gang leader. With a vision handicap that required me to wear these giant goggles, I was especially partial to a civilized society. The most important thing is getting along with your neighbors… if you can recognize them more than 20 feet away.

That left a problem: Without the promise of boundless rewards and diabolical punishments, could others be socialized and made interdependent? Was religion, like Santa Claus’s short-term carrot and stick or a boogeyman to scare them straight, just something we teach our children to civilize them until they’re old enough to more or less fit in and obey the rules?

Would it be possible to discern or to craft a universal religious ethic that would tighten up the frayed ends of our economy’s highest and lowest, most ruthless classes? A science-based doctrine such as Evolutionary Psychology seemed to suggest itself, emphasizing species cooperation and the vital interdependence of our human community. But in recent chat room mud ditches, I’m told, evolution has become a stronghold of Social Darwinian survivalists extolling unlimited fierce competition and “nature red in tooth and claw.”

Due in part to this unbridled (and illusory) self-interest, we face a literal and fatal global meltdown. It becomes abundantly clear, with or without guidance from above, that the miracle of earthly life that brought us here, and that may yet sustain us, is the true Gospel we should preach and heed.